Kenny Hill arrived in Chauvin, La., stayed 12 years and then disappeared in January 2000. He didn't organize a rummage sale or pack up a U-Haul; he abandoned his personal possessions in his sudden flight. Above the kitchen sink he painted a sign in red: "HELL IS HERE, WELCOME."

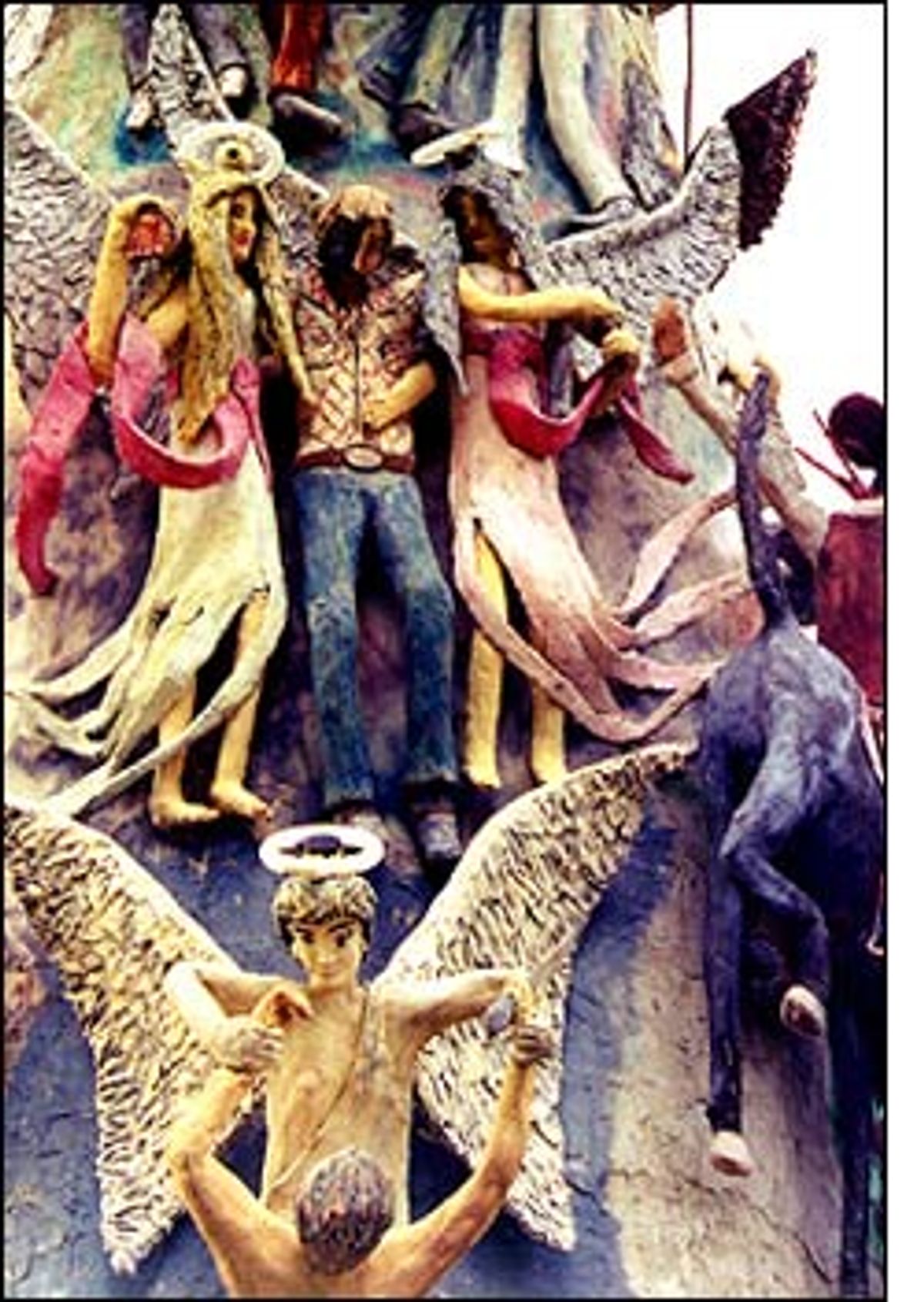

Few would have paid any attention to his vanishing act had Hill not left something behind. On the banks of Bayou Petit Caillou, dotted with shrimp boats, more than 100 brightly painted sculptures mark Hill's stay in Chauvin (pronounced show-van, population 3,400). Many of the pieces are made from cement and wire mesh, though the most prominent, a 45-foot-tall lighthouse, is composed of 7,000 bricks. Figures in relief stud the outside: musicians, cowboys, soldiers, angels, God and Hill himself.

Before Chauvin, Hill worked as a bricklayer in a town 60 miles west. After leaving his three children and the woman he married at 20 (when she was 14), he rented some property on the bayou in Chauvin for $250 a year in 1988. He lived in a tent while he did bricklaying jobs and built himself a small cottage. Then in 1990, without explanation, he started making religious scenes beside the house. Like many other self-taught or "outsider" artists, he was a resourceful scavenger, lifting sand, cement and bricks from nearby work sites. A neighbor welded the underlying metal armature for some of the sculptures.

Hill spent a decade working on his art without giving a thought to profit, according to those who knew him. This idea of making for making's sake is part of what Roger Cardinal meant when he coined the term "outsider art" in 1972, a translation of the French "art brut" first used by artist Jean Dubuffet in the 1940s. Cardinal describes this art as "not hooked up to galleries ... it should be more or less inwards-turning and imaginative." He goes on to explain how this definition is fairly easy to use when categorizing the work of a dead artist but can become problematic when dealing with the living, who "might at some point, after all, go to their own openings and begin to be interviewed."

Howard Finster is perhaps the best-known outsider artist to actively enter the world of profit -- to the point of becoming a cottage industry. In his Paradise Garden in Pennville, Ga., Finster makes what he calls "sermons in paint." His fame spread via newspaper articles and TV appearances and then through pop culture after R.E.M. and the Talking Heads commissioned album covers from him. His Web site encourages visitors to call the 800 number and buy, buy, buy. At an auction in October, the price of pieces started at $300, but Finster didn't want anyone to lose out. "If you cannot afford a Howard Finster piece," the site suggests, "his daughter, Beverly Finster, is now re-creating his pieces for approximately 1/3 the price of a Howard Finster Original."

Hill may fit into a subcategory of outsider art -- "psychotic art." Cardinal finds in this genre "a quality of urgency, and sometimes quite fearful urgency, which can give ... viewers a particular emotional shock."

The reclusive 45-year-old Hill certainly came across to locals as disturbed, and several tried to help him before he vanished. A story in a regional paper described Hill as "an eccentric who was completely obsessed with his biblically themed sculptures."

Frederic Allamel, a French art sociologist, first noticed Hill's project in 1992. He remembers a handful of sculptures, most with only the armature in place, and the partially built lighthouse. He returned to Hill's site in 1999. On this visit, Hill came out of his house and started to talk about his work.

"He spoke as if he were in a trance," recalls Allamel, who describes Hill's monologue as irrational, spiritual and schizophrenic. "There was no chance for me to say a word."

Dennis Siporski, who looks a bit like Dennis Hopper, has devoted a fair amount of time over the past year to preserving Hill's work. Siporski chairs the art department at Nicholls State University, about 30 miles north of Chauvin. The artist entered his radar in the fall of 1999. Siporski was on his way to Louisiana's Barrier Islands when he passed the carnival of figures.

He saw angels everywhere: Teams of two, armed with swords, protect gateways; one sits playing a harp; another holds an hourglass; three have their arms in the air and their heads thrown back in celebration; sterner angels point the way to eternity. Three flying angels accompany a procession of 11 figures winding their way along a brick-lined path. Hill placed himself in many of the tableaux. He rides a horse, or he carries Christ's cross and stands with long hair and a beard, his heart bleeding, in a circular cement base inscribed with the message "It is emty [sic]."

Siporski was so entranced that he returned soon afterward to take photographs and interview Hill. When Siporski spoke with him last fall, Hill hadn't touched any of the pieces all summer. "This part of my life is done," Hill told Siporski. Siporski tried to get him to expound on the site's meaning.

"Is this your vision?" Siporski asked.

"It's about living and life and everything I've learned," Hill replied.

Siporski gently urged him to be more specific. Instead, Hill got vague. "It was like talking to a guru -- very Zen," Siporski recalls. "It was my job to find out what it meant. If he had to explain, I obviously didn't get it." Hill talked on and on and on about wanting people to come and experience his dioramas, and he was not unintelligent.

"If he'd cleaned himself up and put on a suit," Siporski says, "you'd think he was an old college professor, talking about how it takes the whole being to make art. He was way beyond art as a thing."

A recluse doesn't make a lot of acquaintances, and tracking down information on Hill is an uphill battle. No one in the office at Patterson High School remembers him, nor can anyone find a record of him graduating. In Chauvin, most people never laid eyes on him. He never wandered into Sportsman's Paradise just across the bayou, though a waitress there heard he was "odd in the head and temperamental."

As nobody knows Hill, nobody knows what triggered his abrupt departure. At the fire station next to the library, one of the firefighters speculates that financial problems drove Hill away. As Siporski pieces it together, Hill misunderstood his obligations to the IRS: He seemed to think the government was going to take any money he made, so he stopped working. Soon he could no longer pay the rent. Then his mother died. Siporski believes Hill's sense of loss was intensified by increasing guilt about the limited contact he maintained with his children after he moved to Chauvin.

Over at Danny's Fried Chicken, patrons suggest he went overseas to make money. Customers at the Pizza Express disagree. They say he took off for Arkansas to hide in the woods near his brother. Siporski, Allamel and Hill's former neighbor, Julius Neil, concur. Some of the locals use the Cajun expression "comme une bétaille" -- like a wild beast -- when describing Hill's existence in lands farther north.

According to Neil, who knew Hill the entire time he resided in Chauvin, "Kenny loosened up about six months before he left. He wouldn't talk right and raised all kinds of hell." Before then, Neil had found Hill to be a good neighbor. If Neil was cutting the grass and Hill came by, he'd stop to help. Neil has his own explanation for Hill's departure. "The landlord came to collect the rent money, but Kenny felt he owned the land. He got sassy with the landlord and was evicted."

The couple who owned the property where Hill lived put it up for sale immediately after he left, though they were skeptical that any buyer would want it with the huge sculpture garden. Siporski could have purchased the land himself and sold the pieces to collectors for thousands of dollars, he says. Over the past 20 years, folk and outsider art has become big business. But the idea of auctioning off Hill's vision turned Siporski's stomach. He met with the owners to discuss the aesthetic value of the site and begged for some time to explore how to preserve the sculptures. The couple agreed.

To drum up support, Siporski invited faculty from art departments at Nicholls and Louisiana State University to come take a look. Greg Elliott, head of the sculpture program at LSU, said, "I've spent most of my life looking for folk art and this is really a remarkable site." Still, neither of the colleges could fund a full conservation effort.

Siporski remembered the Kohler Foundation in Wisconsin, which had restored another "art environment" along the Mississippi River, and, on a whim, Siporski called. Executive director Terri Yoho took an immediate interest and some foundation members flew to Louisiana to talk with the property owners.

At the same time, Siporski approached the president of Nicholls, Donald Ayo. "The president is an art lover and within 10 minutes agreed to have Nicholls take over maintenance of the site once Kohler finished restoration," says Siporski. On May 2, the foundation purchased the property. The foundation has participated in the preservation of seven self-taught artists' environments in Wisconsin, but this is its first project outside the state. No one involved will make any money from Hill's art.

Next year, construction of a visitor and education center will start across the road from the site. Siporski dreams of a day when people will be able to stay at the center, take time to really look at what Hill made from every angle and create their own sculptures in response. These would become part of a new, ever-growing sculpture garden.

Those working to protect what Hill abandoned find themselves in an uncertain position. After spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars -- they cleaned and sealed all the sculptures, and obtained an Army Corps of Engineers permit to build a bulkhead to protect the art from flooding -- they don't really know how Hill would react to their efforts. Hill took obvious pride in his salvation scenes but also hated publicity. Kohler Foundation project coordinator Michele Gutierrez, who inventoried and mapped the site, worries about a story a neighbor told her: Supposedly, Hill burned a houseboat he'd built when a picture of it appeared in a magazine. But Neil believes Hill will stay away: "He left and it's out of his mind."

Gutierrez never met Hill, but she carefully went through the personal effects he left behind. "This [art] was created by a person in great strife," Gutierrez says, "but Kenny ... deserves respect and empathy. The art says it all -- the poignant and the solitary, the grand and the low, the humorous, the fearful, the hoped for. It is the story of life: Kenny's, mine, everyone's."

Shares